“One can survive everything, nowadays, except death, and live down everything except a good reputation” – Oscar Wilde

Its hard work being a saint. That’s why most of us don’t bother trying. Or maybe it’s the easy accessibility of alcoholic beverages. Or TikTok. One would figure that there are few enough saints in the world, that we probably know all their names. One would be wrong. The Catholic Church recognizes around 10,000 saints (although there is some wiggle room, as this includes the “venerable” and “blessed”, but they are generally on the short track to canonization, and just need to add a few miracles to the resume), and the Russian Orthodox Church recognizes about 5000 (about half are specifically Russian), but these are estimates, as the biographies of many of these saints are lost to time. Who knew misplacing saints was a thing? Just another cross a saint has to bear, I guess.

The problem with being dead, apart from the boredom, the smell, desiccation of one’s flesh, and perhaps the Lake of Fire should you have led an especially unsavory life, is that you ultimately lose control of your branding. Business magnate Henry Ford once said, “You can’t build a reputation on what you are going to do”. This is undeniably true, but presents, dare I say an existential problem when you’re dead, as you aren’t really going to do anything except rot, which is not generally considered a useful touchpoint for marketers outside the funeral industry. The obvious solution is not dying, but experts agree that is rarely an option. You might be able to haunt whomever misuses your reputation, but given the relative dearth of ghosts – I mean, if everybody became a ghost, we should have about 100 billion specters lurking in the shadows and consequently, a whole lot more ghost-hunting reality shows; obviously, there is a division of the afterlife concerned with standards and practices – it’s clear that eventually even throwing plates, banging doors, scaring the family pets, and getting all phantasmagoric must get tedious. No, once you’re dead, unless you made arrangements for some pretty savvy posthumous legal representation ad infinitum, history pretty much owns you and your carefully built reputation.

Take poor Prokhor Moshnin (1754-1833 AD), later known as “Saint Seraphim of Sarov”. By all accounts he was a pretty decent guy. Momma didn’t raise no sinner in his hometown of Kursk, Russia. Suffering from a childhood illness, he was miraculously healed by a famous icon called the “Kursk Root Icon of the Sign” (an icon of the Virgin Mary found in the forest near Kursk in the 13th Century), after which he started having visions. At the age of 19, he joined the Sarov Monastery, took his monastic vows nine years later, and seven years after that became the spiritual leader of the Diveyevo Convent in Nizhny Novgorod. Not long after this elevation, he retreated to a log cabin in the woods near the Sarov Monastery and became a hermit for the next 25 years, because hey, spiritual leadership is a distracting business when you’re busy getting your God on.

At this point the Seraphim of Sarov went for gold in the saintly Olympics. He had a strict fasting regimen, eating only bread from the nearby monestary and vegetables from his garden (occasionally subsisting only on grass), making friends with the woodland animals, including a rather intimidating bear. He was reportedly attacked by thieves who beat him savagely, resulting in the hunched back he would have for the rest of his life – he returned to the monastery to recover, but did not neglect to plead the court for mercy on the behalf of the thieves at their eventual trial. After 5 months recuperating, he returned to the wilderness, and spent 1000 successive nights on a rock in continuous prayer with his arms raised to the sky. In 1815, he started to allow visitors to his little hut in the woods, where he dispensed wisdom, prophecy, and is said to have had remarkable healing powers (there are some rumors of levitation). He never wrote anything, but is most famously quoted as saying, “”acquire a peaceful spirit, and thousands around you will be saved.” Basically, he was just insanely nice and mellow.

Seraphim was fifty years old when he returned to the monastery, but for another five years he remained a recluse in his cell. Then, after more than thirty years of solitude and prayer, he opened the doors of his cell to all those who needed his guidance and advice. All of his visitors were received with a curious mixture of humility and authority. For eight years thousands of people from all walks of life came in crowds to the Monastery of Sarov and brought to St. Seraphim their problems, their sorrows, and their sins. Frequently he answered questions before they were asked, and upon his death in 1833, he left scores of unopened letters from writers who had already received his answers (Koulomzin, 1963, p198).

It’s no surprise, given his personality and essential saintliness, that only some 70 years after his death, the Seraphim of Sarov was canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church, although there was some concern that his corpse was not actually “incorruptible”, like some other saints. They dug him up to check, but decided the fact that he was rather fetid wasn’t a deal-breaker when it came to sainthood.

On August 1st, 1903, in the peaceful forest where lies the monastery of Sarov, the ceremony of the canonization of St. Seraphim of Sarov took place. Thousands of people from all parts of the country flocked to the spot, eager to kiss the blessed relics of the saint. The Tsar, with the Tsarina and the Dowager-Empress, came to join with the people in praying to the miracle worker of Sarov. On July 31st, the eve of the ceremony, their Majesties received the Sacrament at early service in the Cathedral of the Assumption. The congregation were deeply impressed by the sight of the Emperor and Empress in their midst as simple pilgrims, unattended by any suite (Elchaninov, 1913, p78).

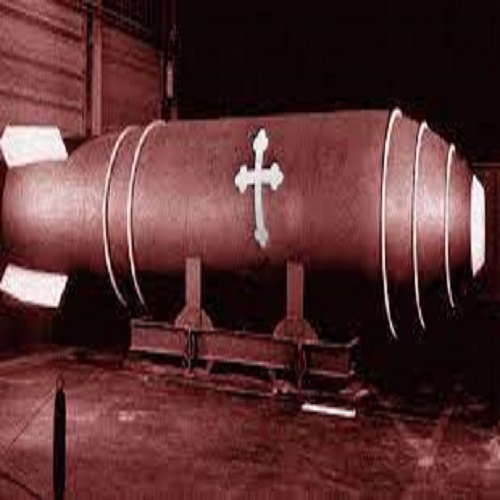

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, and the resurgence of the Russian Orthodox Church, priests have been seen sprinkling holy water on submarines, rockets, jets, tanks, and ballistic missiles. And ultimately, as it turns out, Russia’s nuclear arsenal also has its own patron saint – none other than St. Seraphim of Sarov. This was explained concisely to an America diplomat.

One of the spokesmen from the military industrial complex at this conference said that, unlike the American bomb, the Russian bomb is moral, because the Russian bomb was developed near the homeland of St. Seraphim of Sarov, and therefore is under the blessing of St. Seraphim. That auditorium on the grounds of the Danilovsky Monastery, the headquarters of the Moscow Patriarchate, was full of Orthodox priests. I didn’t hear any of them protest that statement (United States Congress, 1997, p10).

In 2019, the Russian Orthodox Church started debating whether they should be blessing weapons of mass destruction, and in 2020 concluded that priests should refrain from the practice. This makes sense, as I strongly suspect that atomic holocaust is sort of off-brand for Saint Seraphim of Sarov, but having the lack of foresight to die before they were invented, he didn’t really get a say in the matter. Despite the obvious hardships, maybe you’re thinking of getting into the saint racket? Consider George Orwell’s observation, “Many people genuinely do not want to be saints, and it is probable that some who achieve or aspire to sainthood have never felt much temptation to be human beings”. Oh, and get a good estate lawyer.

References

United States Congress. Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe. Religious Freedom in Russia: January 14, 1997: Briefing of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe. Washington, DC (234 Ford House Office Building, Washington 20515-6460): The Commission, 1997.

Elchaninov, A. G. (Andreĭ Georgīevich), A. P. W., and Akademie der Pädagogischen Wissenschaften der DDR. Tsar Nicholas II. London: Hugh Rees, 1913.

Koulomzin, Sophie, 1903-. The Orthodox Christian Church Through the Ages. [Rev. ed.] New York: Metropolitan Council Publications Committee, Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church of America, 1963.