“M. de Maupassant sees human life as a terribly ugly business relieved by the comical, but even the comedy is for the most part the comedy of misery, of avidity, of ignorance, helplessness, and grossness” – Henry James

Speaking with his novelist friend Paul Bourget, prior to writing Le Horla, Maupassant confessed that he frequently encountered his own double, and while he repeatedly assured himself that it was pure hallucination, he recognized that his mind was starting to slip.

“Every other time I come home, I see my double. I open my door, and I see him sitting in my arm-chair. I know it for a hallucination, even while experiencing it. Curious! If I didn’t have a little common sense, I’d be afraid.” (The possibility of his perpetrating a hoax, saying something to shock, must always be kept in mind, though he was probably less likely to do so with Bourget than with others.) In his moments of mental distress he quite possibly had some kind of presentiment, at this time still unformulated, of all not being well with himself; and his presentiment he tried to “shed in books.” In Le Horla Maupassant is probably the opposite of a sufferer from a stroke, who, understanding others perfectly, nevertheless cannot express himself: in the story he gives disciplined, perfect expression to hallucinations and fears which he does not understand, and which have not yet troubled him to the extent of making him incapable of his own, superior, artist’s utterance (Steegmuller, 1949, p256-257).

Thoughts of disassociation from himself, visual and auditory hallucinations, and increasing despondency seemed to consume him, and even his secret paramour (possibly the mysterious Gisèle d’Estoc) who would later pen a “Love Diary” describing her scandalous relationship with Maupassant including procuring other women for him, described a frightening turn in his character.

Even the favoured and mysterious love of his life, who absorbed so much of his thoughts and companionship at this time, noticed how curiously he behaved. In the diary made by him from the paper which he used for his stories, “bound in dark blue leather, with silver stars,” she noted that he would suddenly stop in the middle of a sentence, complaining of many voices in his ears which sounded as if they came from a pit. The face he saw in the mirror was not his. Her “hero” and her “god” was often melancholy when he arrived at their rendezvous in Passy, and the not very brilliant conversation which she remembered was full of references to the oppression of twilight “like a shroud over Paris,” and to the brevity of all happiness (Boyd, 1926, p189-190).

Not long after, Maupassant would write Le Horla. Or rather, his doppelganger arrived to share the story with him.

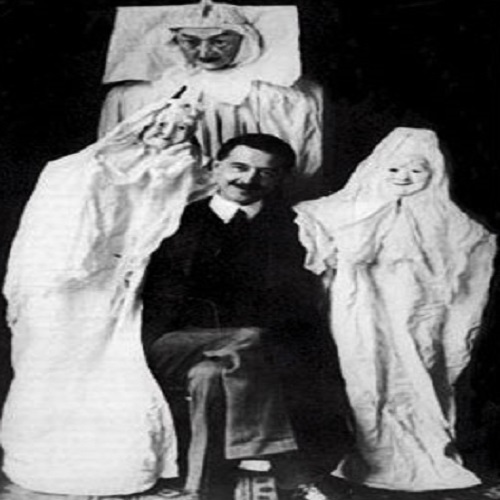

One of his close friends told me that in 1889, Maupassant had a vivid hallucination one afternoon and told his friend of it that evening. Working at his desk in his office, where his servant had orders never to enter while he was writing, he seemed to hear his door open. He turned and was not a little surprised when he himself [Maupassant’s double] entered, and came to sit in front of him, head in hand, and began to dictate everything he wrote on the occasion. When he had finished and stood up, the hallucination disappeared. The result was the short story Le Horla (Sollier, 1903, p11).

To Maupassant’s closest friends, Le Horla seemed to mirror what he claimed were his own experiences, and a complete mental breakdown seemed imminent.

I am certain now, that there exists close to me an invisible being that lives on milk and water, that can touch objects, take them, and change their places. It lives as I do, under my roof. I have seen mad people, and I have known some who have been intelligent, lucid, even clear-sighted in every concern of life, except on one point. They spoke clearly, readily, profoundly on everything, when suddenly their mind struck upon the shoals of their madness, and broke to pieces there, and scattered and foundered in that furious and terrible sea, full of rolling waves, fogs and squalls, which is called madness. I spent a terrible evening yesterday. He does not show himself any more, but I feel that he is near me; watching me, looking at me, penetrating me, dominating me; and more redoubtable when he hides himself thus than if he were to manifest his constant and invisible presence by supernatural phenomena (Maupassant, Le Horla).

Maupassant’s behavior became stranger and stranger, and his valet Francois would later recollect the events leading up to Maupassant’s two suicide attempts.

The story of the actual breakdown has never been made quite clear. Francois hintingly attributed it to the “lady of the pearl-grey dress and golden waistband,” and to a mysterious telegram from an eastern land. There was a journey to the Ile-Sainte-Marguerite during which some weird and horrible thing happened. But what it was no one seems to know. A week later, at Cannes, Maupassant made two attempts at suicide. Then he had the delusion that war had been declared between France and Germany. He was feverishly eager to go to the front and made Francois swear to follow him to the defense of the eastern frontier. “During our numerous journeys,” recorded Franois, “he always gave me his military certificate to take care of, for fear this should be lost in the enormous quantities of papers he possessed.”

Finally, Maupassant was committed to a private asylum, where he died in 1893.

Then again, and for the last time, Paris, or rather the outskirts of Paris; the maison de sante of Doctor Blanche at Passy, where he was to remain till the end. They are not pleasant to contemplate, those last days. There were periods of gibbering and violence. He imagined countless invisible enemies. Even against the faithful Francois he turned, accusing him of having taken his place – on the Figaro and slandered him in heaven. “I beg you to leave me; I refuse to see you anymore.” In a savage moment he hurled a billiard ball at the head of another inmate. Again his madness would take the form of belief in his own Monte- Cristo-like wealth — the folic des grandeurs — when he would rush about calling to an imaginary broker to sell the French rentes, en bloc (Maurice, 1919, p175-176).

In the late 19th Century, psychiatry was on the rise, and Maupassant himself attended lectures by founder of modern neurology Jean-Martin Charcot. His repeated encounters with his doppelganger were simply chalked up to his progressive descent into madness, although expressed puzzlement at the way, given this interpretation, that Maupassant remained intellectually prodigious even as his mental state degenerated.

One of the most interesting studies of incipient insanity is Le Horla, by Guy de Maupassant, who was probably drawing upon his own sad experiences when he wrote it. It shows how the senses may become increasingly liable to error those senses which are accepted as our best, if not our only guides to the nature of the outer world, sight, touch, and hearing, and how this form of cerebral affection may be attended by a progressive derangement, ‘weakening’ is not the word, of the reasoning and reflective faculties. That way, of course, lunacy lies. But undoubtedly hallucinations of the senses may exist without any impairment of the intellect. Not only so, but they may be stimulated in certain cases by the mere association of ideas, or a vivid expectation of something (Nisbet, 1899, p98).

Maupassant was consumed with depicting human lives as the embodiment of disillusion, and helplessness before social forces – a theme that permeates even his non-supernatural writings. He saw alienation and madness precipitated by the close of the 19th Century, the waning of Romanticism, and rapid scientific progress driving forward man as machine, controlled and controllable, and in an increasingly interconnected world, he sought solitude, only to be pursued by his doppelganger. He may have been more lucid than the rest of us, as Miguel de Cervantes suggested when he said, “Too much sanity may be madness and the maddest of all, to see life as it is and not as it should be”.

References

Bourget, Paul. “Two Séances at the house of Mrs. P. at Boston.”Annales des Sciences Psychiques, 1895.

Boyd, Ernest Augustus, 1887-1946. Guy De Maupassant: a Biographical Study. New York: A.A. Knopf, 1926.

Grasset, J. 1849-1918. The Semi-insane And the Semi-responsible. Authorized American ed., tr. by Smith Ely Jelliffe. New York: Funk and Wagnalls, 1907.

Maupassant, Guy de, 1850-1893. The Life Work of Henri René Guy De Maupassant: Embracing Romance, Travel, Comedy And Verse, for the First Time Complete In English. [Éd. de luxe] London: Printed for subscribers only by M. W. Dunne, 1903.

Maurice, Arthur Bartlett, 1873-1946. The Paris of the Novelists. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1919.

Nisbet, John Ferguson, 1851-1899. The Human Machine: an Inquiry Into the Diversity of Human Faculty In Its Bearings Upon Social Life, Religion, Education, And Politics. London: G. Richards, 1899.

Sollier, Paul Auguste, 1861-1933. Les Phénomènes D’autoscopie. Paris: Alcan, 1903.

Steegmuller, Francis, 1906-1994. Maupassant, a Lion In the Path. -. New York: Random House, 1949.

Was Maupassant an atheist? It seems he was actually hostile to religion, and became embarrassed by experiencing inexplicable (for him) phenomena (popularly explained by syphilis). Perhaps the lesson here is that convinced atheists should always avoid two things -syphilis and “supernatural” manifestations.

Thanks to the author for this piece. Sounds to me as if this Maupassant was either possessed or oppressed by a dark, evil, negative entity that fed on the positive brilliance of an artist and writer – maybe someone from his past, his childhood?

Absolutely love this, fascinating. Who knows what dark things lurk in writers minds?

Many thanks. I like to maintain a healthy state of paranoia about writing…