“If you can keep your head about you when all about you are losing theirs, it’s just possible you haven’t grasped the situation” – Rose Kennedy

Thomas E. Moss (d. 1960) was named after his father, Confederate Major, distinguished lawyer, and Attorney General of Kentucky, Thomas E. Moss. Thomas Junior was born In Paducah, Kentucky, eventually becoming a physician and settling in Woodville, Kentucky. His brother Jesse and sister Marie both followed in the footsteps of their father and became lawyers (Marie was the second woman ever admitted to the Kentucky bar), thus Thomas Jr. was likely left wondering how he could measure up to his father’s lofty legacy. So he joined the United States Army. But in 1905, we weren’t really engaged in any major international conflicts that an adventurous young doctor could sink his bone saw into. The Spanish-American War lasted only about four months and concluded in 1898 with the Treaty of Paris. One upshot of the treaty was the Spanish ceding of the Philippines to the United States.

The First Philippine Republic was no more happy at being an American possession then they were at being a Spanish one, resulting in the bloody, atrocity and cholera-filled Philippine-American War (1899-1902) ending with the American occupation of the Philippines, a state of affairs that lasted until the Japanese arrived to make everybody miserable in World War II. But by 1905, the U.S. military had settled in for the duration, even though hostilities persisted in some remoter regions until 1913. The Journal of the American Medical Association noted in 1905 that “Dr. Thomas E. Moss, Woodville, sailed from Seattle August 31 for the Philippine Islands” (JAMA, 1905, p797).

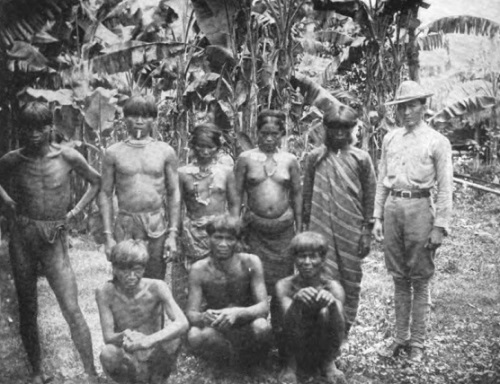

The U.S. Military had been gradually turning over policing responsibilities to the Philippine Constabulary, although most of the officers were still U.S. military men as were many governmental positions. The Official Roster of Officers and Employees in the Civil Service of the Philippines Island, compiled in 1905, lists Thomas E. Moss of Kentucky as a 1st Lieutenant and Medical Inspector, appointed to the Philippine Civil Service on October 15, 1905 at 3200 dollars per year. Moss was assigned command of a hospital in Tuguegarao, the capital of Cagayan province. At the time, the Cagayan Valley was fairly quiet, but in the mountains surrounding lived the Kalinga tribes, renowned for their head-hunting. In the course of his duties, Moss was assigned to an expedition to explore and map the rarely visited mountainous regions, and happened across the rancheria Nanong (a small cluster of mountain villages) and a long-suffering Kalinga chieftain who had been tormented by an agonizing stone in his bladder for years. Noting that Moss was a man of medicine, the Chief asked for his assistance. Moss did not have any medicine that would have helped, but explained to him that if he could come to his headquarters at Tuguegarao Hospital in the valley below, he would gladly perform the necessary surgery.

By the time Moss returned to Tuguegarao, a delegation from Nanong had arrived asking that he accompany them back and heal the chief, who was (1) physically unable to travel without assistance, and (2) unable to bring enough men with him to guarantee his safe passage through the hostile village of Tabuc on the way to Tuguegarao without depleting his own village defenses and inviting attack in his absence. The Kalinga chief promised lavish presents in return (including a wife). Moss came up with a compromise. He negotiated a deal with the Kalinga of Tabuc, asking them to allow the chief and a few men to come to Tabuc, where he would perform the surgery. Understandably he was looking for neutral ground, as he was concerned that if the operation went badly he was likely to lose his head. The Nanong representatives agreed. Moss gathered up his Filipino translator and guide Esteban Turingan, his corpsman Miguel Guttierrez, and his surgical equipment and headed for Tabuc to await the chief.

The chief never showed up and it became clear he wasn’t coming. Moss and company decided to do a little deer hunting in the plains below Tabuc with some local Kalinga friends. In the thrill of the hunt, they neglected to notice that some 300 Nanong warriors had quietly surrounded the hunting party, 40 of whom had been detached to capture Moss and his corpsman. Outnumbered some 15 to 1, the friendly Kalinga decided to bug out (all but 6 managed to escape, and those who didn’t had their heads chopped off and collected as trophies). Moss and Guttierrez were marched into the mountains and presented to the Nanong chief, lying on the floor in agony, who offered him the option of curing him or paying the penalty for failure with a summary beheading.

Moss was pretty sure his cranium was going to wind up adorning a Kalinga pole as the conditions were not exactly ideal for surgery. He rigged an operating table, had scalding water poured all over everything, scrubbed the Chief raw with soap, dosed him with quinine and calomel, knocked him out with chloroform, cut into his patient, and removed the offending stone. Guttierrez nursed the Chief night and day, barely daring to sleep. On the tenth day after the operation, the Chief had recovered adequately. A feast was held, and Moss was celebrated and presented with a beautiful headaxe, spear, and shield, as well as a wife (whom he had to decline, as Mrs. Moss would have objected strenuously). The next day Moss and Guttierrez were sent home with an entourage of a dozen Kalinga warriors to escort them as far as Tabuc. Sadly, after a day of travel a runner arrived from Nanong announcing the chief had taken a turn for the worse, at which point Moss and Guttierrez were disarmed and the warriors prepared to haul them back up the mountain. Moss realized there was no way this ended well for him. Moss pointed out that they were all exhausted and that he would happily return and stay for a month to ensure the Chief’s health. All agreed this was optimal and they encamped for the night, breaking out the “Bassi” (a sugar-cane based alcohol), which through a little trickery, Moss managed to dose with copious amounts of morphine by dissolving it in water, which he spat into the jug that got passed around while pretending to drink. A bit of a problem with this plan. He got a nice dose of morphine himself.

The Nanong were sound asleep, save a single guard, who had simply not consumed as much Bassi, knowing he needed to be relatively alert. Clearly the morphine had affected him, but the guard was struggling hard to stay awake. Corpsman Guttierrez snuck behind the guard and dispatched him with a headaxe, but his headless corpse convulsed, waking two of the other warriors, who Moss and Guttierrez had no trouble knocking unconscious as they were still heavily doped. They quickly made their escape, all the while fearing the vengeance that the Nanong would exact when their Chief died. This was not to pass. The Chief actually recovered fully, and Moss’ reputation among the Kalinga as a solid medicine man was firmly established. They even chose to overlook the murdered guard.

Now this reads like a raucous tale of death-defying adventure that oddly was reported by Moss in a three part series written for the American Journal of Clinical Medicine in 1912. And while we can attribute some of the “Heart of Darkness” bombast to the style of the times, Moss finished his story with an exceptionally strange report.

One night, many months after I had returned from this eventful trip into the headhunters’ domain, I was sitting in my office finishing up the monthly reports, which I was bound to get off in the morning’s mail, so that they would reach Manila in time, and as there were many of the papers, I had to work late into the night. My corpsman, who had accompanied me on that trip, was sitting at his desk, over against the wall, assisting in my work. His desk stood directly beneath that space on the wall which I had devoted to my curios, such as axes, spears, various other weapons, besides prepared heads and other native curiosities. The weapons were arranged in groups and hung by nails driven into the plaster of the wall. It must have been one o’clock in the morning—I was leaning back in my desk-chair watching the Filipino at his work, while occasionally glancing up at the murderous tools, letting my mind wander leisurely over the history attached to some of them, fixing my attention especially upon that headaxe of the Kalinga sentinel whom my corpsman had beheaded, at the same time observing that it hung directly over the latter’s head. This ax was conspicuously beautiful, being ornamented with brass and silver. In my mind’s eye I could see the drowsy Kalinga warrior as he started to rise, and how then the corpsman severed his head with a fierce blow; I could see the convulsive movements of his headless body as it jerked and writhed upon the ground; I went over every foot of that awful trail and reconstructed every happening of the horrible experience. Then, as I saw each threatening face of that savage band rise before me, I fancied that I heard soft foot-falls approaching the door of my office, and I looked up, expecting to see a servant enter to tell me to come on home, for my good wife always would sit up and wait for me whenever I was delayed at the office at night.

What was my horror, to see the door open and two Kalingas step into the room and glide softly toward the corpsman, who was working steadily away and did not seem to notice the men as they approached him. Looking closely, I was struck dumb to see that both Kalingas had their headaxes raised for the deadly stroke I knew so well. I tried to call a warning, but could utter no sound; but I sprang to my feet as the fatal blow fell. I saw the headaxe cleave the air, I saw it strike the man in the neck, I saw him fall to the floor; I saw him staggering to his feet, uttering a piercing cry of pain, then totter and fall. As he struck the floor, the Kalinga men vanished, but as they faded from sight I saw that one carried the dead man’s head in his hand—it was the Kalinga sentinel! I rushed over to the corpsman. He was sitting on the floor trying to stop the flow of blood that was spurting in every direction. Snatching up an artery-forceps, I caught up the severed ends of the arteries, then laid him on the sofa and proceeded to sew up the wound. Having finished the dressing, I bethought myself of the Kalingas and of the headaxe which I had seen them drop on the floor. I went over to it, thinking that possibly it might help in identifying the assassin; but, picking it up, what was my surprise to recognize it as the headaxe taken from the slain Kalinga sentinel. The weapon had been hanging on the wall of my office for many months, and knowing this, I can assure you that I began to have creepy feelings and to wonder whether I was sleeping, or dreaming, or what. Then, looking up to the place on the wall where the ax had been suspended, I saw that it was not there. As to whether that ax had become loosened and fallen and in its descent had struck the corpsman in the neck, or whether the spirit of the dead sentinel had come to avenge himself, I do not pretend to know. One thing is certain: to me the strange occurrence in that gruesome midnight hour will for all time remain an unsolved mystery (Moss, 1912, p374-376)

This visitation from phantom headhunters was not entirely consistent with the belief system of the Kalinga. Normally, “The head-hunting expeditions of the Kalingas are carefully planned in advance, and a plan of campaign once formed is carried out as closely as circumstances will permit. A band of forty or fifty warriors may be on the trail for days before they reach their objective point. The combat is usually begun from ambush, and is of short duration. The man who first reaches the enemy is the leader. As soon as either side has a combatant down, it concentrates its efforts on saving his head and to this end tries to get away with him as speedily as possible. Warriors always make a determined effort to secure the heads of enemies killed in battle and to carry them to their rancherias, where they are immediately exhibited in bamboo baskets at the houses of the persons who took them” (Worcester, 1906, p822), but the relatives of the victim of head-hunting were also expected to engage in a reciprocal revenge on the individual responsible. Head-hunting ghosts were not a big thing, since that defeated the purpose of taking the head in the first place (it was regarded as the seat of the soul). The again, Guttierrez didn’t take the head of the slaughtered guard with them when he and Moss made their escape. This may have been a near-fatal oversight. In a slight variation of The Godfather maxim, “Leave the gun, take the Cannoli”, one must undoubtedly “Leave the headaxe, take the head”.

Revenge seems to be a popular motive for angry ghosts. This is obviously our means of trying to communicate that you shouldn’t do anything to others that would merit vengeance from the afterlife. Beheading is probably pretty high on that list. We are given to understand that Guttierrez survived the spectral attack, which suggests the ghost was not as much interested in killing him as making an existential point, for as the director Park Chan-Wook once said, “The point of revenge is not in the completion but in the process”.

References

American Medical Association. “Medical News”. Journal of the American Medical Association v45:1. Chicago: American Medical Association, 1905

Philippines. Bureau of Constabulary. General Orders v328. [Manila]: Bureau of Constabulary, 1909.

Moss, Thomas E. “How I Operated on a Kalinga Chief”. The American Journal of Clinical Medicine v19. Chicago: American Journal of Clinical Medicine, 1912.

Lewis Publishing Company. Memorial Record of Western Kentucky v2. Chicago: The Lewis publishing company, 1904.

Philippines. Bureau of Civil Service. Official Roster of Officers and Employees In the Civil Service of the Philippine Islands. Manila: Bureau of Printing, 1904.

United States. Philippine Commission (1900-1916). Annual Reports.

Worcester, Dean C. 1866-1924. The Non-Christian Tribes of Northern Luzon. [Manila], 1906.